An unprecedented rise in the number of Kenyan women choosing Caesarian section(C-section) deliveries across the country has left insurance firms with huge medical claims to settle as the share of normal deliveries drops.

Multiple interviews with medical insurers, including Jubilee, AAR Insurance and Britam, have revealed that Caesarian section deliveries, commonly referred to as C-section, account for close to 70 percent of their bills for maternity.

For instance, of the Sh1.67 billion that Jubilee Health, one of the largest health insurers in Kenya, has paid for deliveries in the past five years, about 67 percent or Sh1.11 billion has been towards Caesarean section.

Within this period, Jubilee has watched the share of C-sections in the total deliveries that utilised its medical card jump from 42 percent to 58 percent.

While the underwriters are concerned about this trend, they are often careful not to be seen as standing in the way of women perceiving C-section deliveries to be safer than normal deliveries or for a lower social class.

“While there are emergencies that require C-section, there are many women who now say they are too posh to push. So, normal delivery is almost viewed as something for the poor or for those without medical insurance,” said Njeri Jomo, chief executive at Jubilee Health Insurance.

“The moment one walks to the hospital with a medical card, they are almost viewed as carrying an open cheque. To what extent this influences whether it is going to be a C-Section or normal lies our bills pain.”

The latest data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) show that births through C-Section have almost doubled in the past eight years, from nine percent in 2014 to 17 percent in 2022.

Of the 1.24 million hospital deliveries that Kenya had last year, 211,227 were through C-section compared with 110,900 in 2014 when the total deliveries in hospitals were 895,400.

Hospitals such as M.P Shah, Aga Khan Hospital, Nairobi Hospital and Mater Hospital were last year all charging above Sh210,000 for C-section, with emergency C-sections hitting above Sh300,000.

Normal deliveries range between Sh80,000 and Sh100,000 in the same hospitals. The costs have been rising in line with inflation.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) warned in a 2018 guidance note that the “sustained and unprecedented rise in caesarean section rates is a major public health concern.”

The WHO said the ideal rate for C-sections should be between 10 percent and 15 percent and that unnecessary procedures do not come with any proven advantage.

It had also concluded in 2015 that C-section rates above 10 percent were not associated with reductions in rates of maternal and newborn mortality.

“There is no evidence showing the benefits of caesarean delivery for women or infants who do not require the procedure,” said the WHO.

For Kenya, the percentage of C-section deliveries is twice as high in urban areas (23.8 percent) as in rural areas (12.3 percent), according to the KNBS data.

Health facilities managed by faith-based organisations and private medical sector (excluding those belonging to non-governmental organisations) had 28.2 percent and 27.8 percent respectively of their live births delivered by caesarean section.

This is nearly twice the 15 percent in public sector health facilities.

Dr Patrick Gatonga, the chief executive at AAR Insurance Group, said about 15-20 percent of the inpatient cases among women under AAR medical cover are to do with maternity and therefore more C-section deliveries have meant higher claims.

“If you factor in the price differential where charges for C-section is sometimes twice or thrice that of normal deliveries, the cost impact is massive. It is one of the biggest cost drivers of health insurance claims,” said Dr Gatonga.

“C-section poses an outcome impact since if misused, it is not unusual to end with complications, including longer-term ones that ultimately increase the claims towards healthcare covers.”

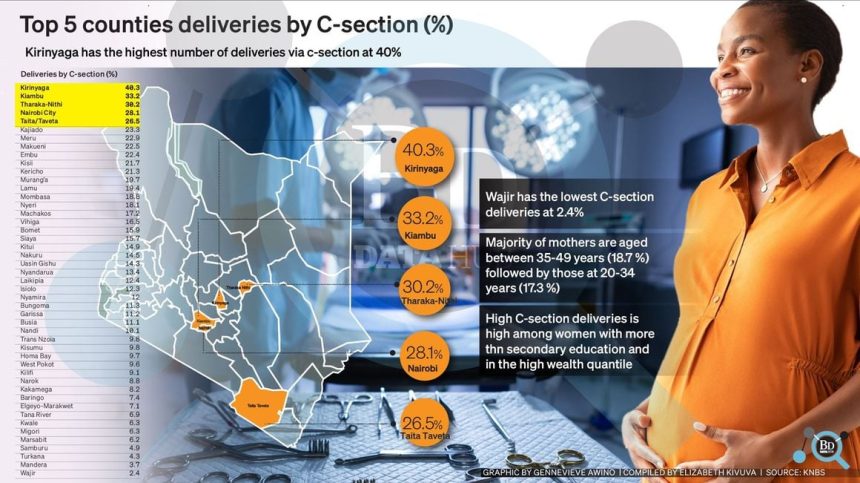

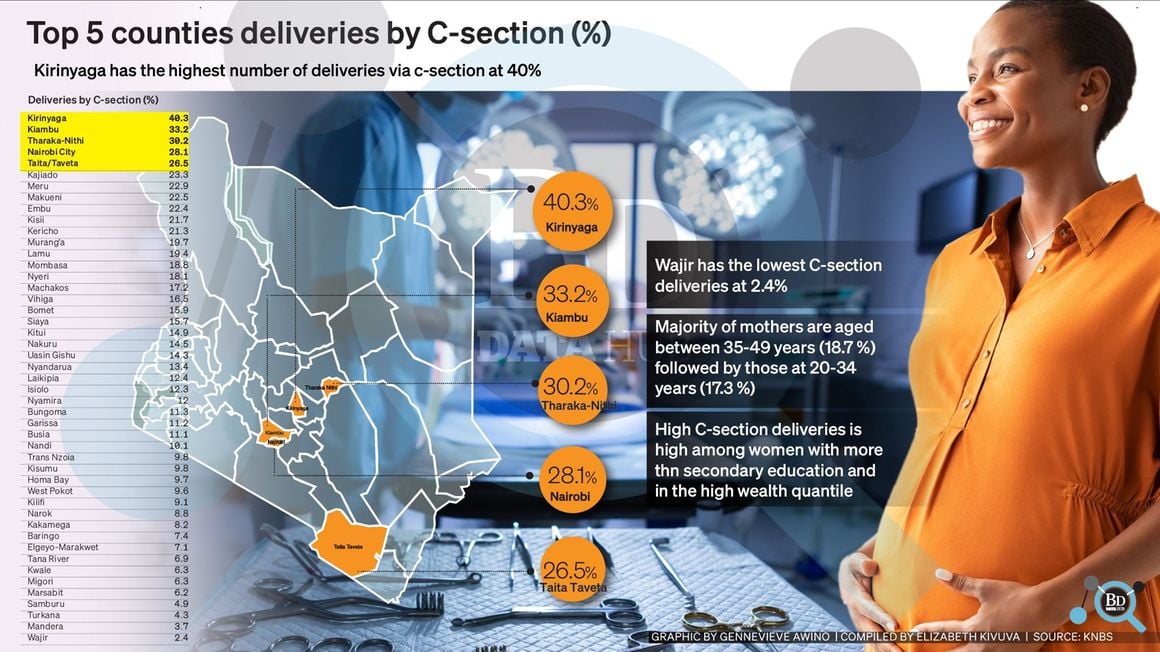

Deliveries by caesarean section in 19 counties are now higher than the expected upper limit of 15 percent compared with 2014 when only five counties— Kirinyaga, Embu, Tharaka-Nithi, Kiambu, and Nairobi— had the share of C-Section in total deliveries exceeded 15 percent.

Kirinyaga has the highest caesarean section delivery rate (40 percent) followed by Kiambu (33 percent), Tharaka-Nithi (30 percent), Nairobi (28 percent), and Taita/Taveta (27 percent).

The counties with the lowest caesarean section delivery rates are Wajir (two percent), Mandera (four percent), Turkana (four percent), and Samburu (five percent).

“The supply-induced demand of C-sections has had a negative impact on the profitability of medical insurance primarily because of the increased cost of care and loading of premium in effect to this utilization,” said Jackson Theuri, the chief executive at Britam General Insurance.

The KNBS survey found that 84 percent of women who delivered by caesarean section stayed in a health facility for three or more days compared with 14 percent of those with normal births.

A longer stay in the hospital usually translates into even higher medical bills.

Jubilee Insurance chairperson Nizar Juma said behind these bundles of joy delivered through C-section has been the silent pain of insurers and doctors who insist that they are simply prioritising their patients’ lives.

“We can mainly put it down to doctors persuading their patients to have a C-section because they get up to four times more money. For patients, whatever the doctor says is like God speaking,” said Mr Juma.

“Doctors are telling their patients that they can decide on the day and time of delivery, that they will not feel pain and can choose a birthday of their choice. I doubt they tell them anything to do with possible risks that come with C-section.”

C-sections can be essential in situations such as prolonged or obstructed labour, foetal distress, or because the baby is presenting in an abnormal position.

But for all its advantages, policymakers such as the WHO say its risks range from short to long-term.

Researchers at Moi University School of Medicine in 2020 published results of a study showing over-use of C-sections based on hospital guidelines was “substantial”, with over four in 10 primary C-sections lacking proper documentation.

Gynaecologist Hillary Mabeya and his colleagues analysed records of 12,209 women who gave birth at the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital in 2014. Their study was published in the International Journal for Equity in Health.

“Our study shows that unnecessary primary C-sections and near-universal repeat C-sections play an important role in explaining both the overall C-section rate and socio-economic inequalities in C-sections,” concluded the study.

“Our study suggests that prevention of unnecessary primary C-sections and promotion of safe trial of labour with close monitoring in women with a scarred uterus could help curb the C-section epidemic.”

Official data show that C-section prevalence increases with the mother’s age, education level, number of antenatal care visits and wealth status.

About 33 percent of live births for women in the highest wealth quintile were delivered by caesarean section compared with five percent of the births for women in the lowest wealth quintile.

Women classified as poor, with little or no education and residing in rural areas record lower levels of C-section, corroborating Ms Jomo’s view that social status and medical cover have a big influence on the method of delivery.