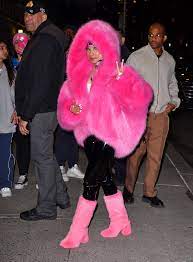

On Monday night, Nicki Minaj made a conspicuous entrance at the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York City to film an episode of “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.” As she walked inside, the formidable rap star was almost completely enveloped by a chunky hooded fuchsia faux fur jacket. A few hours later, she left the taping sheathed in an even larger, full-length version — this time in acid green.

Both coats, which are made from a blend of synthetic fibers (namely, modacrylic and polyester), were courtesy of the French fashion designer Alexandre Vauthier. Custom versions of the outerwear piece have already been worn by Hunter Schafer and Kylie Minogue in recent weeks.

Once upon a time, genuine animal fur was a coveted status symbol. In 1929, Vogue quipped that the fur you wore revealed, “the kind of woman you are and the kind of life you lead.” Almost a century later, it’s still true — though not in the way the magazine intended.

Today, opting for the real deal will likely be seen as a reflection of personal ethics. Tireless PETA campaigning and gallons of red paint have finally swung the pendulum away from fur products; even luxury conglomerate Kering — parent company to designer labels including Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, Balenciaga and Bottega Veneta — phased out fur in 2022.

Making the alternatives to fur desirable remains another challenge altogether, though progress is being made. Just last week, Cardi B made her catwalk debut in a floor-length, bright blue Balenciaga faux fur coat at the label’s pre-fall fashion show in Los Angeles.

But faux fur has, in various guises, existed for over a century (although those reading Vogue in 1929 probably wouldn’t have envisaged it becoming a material of choice for the rich and famous). In the early 1900s, pile fabric — made with the same looped textile technique used to create cord and velvet — was born, with its tufted surface serving as a more affordable alternative to animal skins. Some pile factories of the 20th century became so overrun with orders they had to briefly close production.

In the 1950s, the use of polymers revolutionized the garment industry, offering an even more sophisticated and convincing textile. Striking, unnatural colors began to creep into the market — in a 1957 catalog, a woman models a “fuzzy topper” jacket in baby pink. Fake fur became less about animals and more about artistic abstraction.

In a similar vein, Karl Lagerfeld’s Fall-Winter 1994 collection for Chanel helped make fake fur high fashion. On the runway, ski pants were paired with tall furry docker hats, and cropped fuzzy jackets came in pink, yellow and green. “Like Coco Chanel who mixed fine jewelry with paste — and encouraged other women to do the same — Karl Lagerfeld knew his fur from his fluff,” read Vogue’s show report.

By 2015, fashion’s catwalks were alive with faux fur. Dries Van Noten and Stella McCartney both released collections peppered with silk and modacrylic creations that year. “We like the faux-fur approach because it’s playful and fun,” French designer Julie de Libran told Women’s Wear Daily at the time. “It provides incredible colors and volumes, which are not possible with real fur.”

Debate rages on about synthetic fur’s environmental impact. It’s undoubtedly better for animals, but what about the planet? According to a report released by the Humane Society International earlier this year, a bobble hat featuring a raccoon dog fur pompom has a carbon footprint nearly 20 times higher than its acrylic faux fur counterpart. However, fur alternatives are usually made from plastics, meaning they could take centuries to biodegrade and will likely release microplastics into water systems when washed.

This is seemingly not a conundrum troubling Minaj, who paired her pink faux jacket with a matching pair of — very real — mink fur boots. While she may be heralding in the season’s new it-coat, many will be hoping she leaves her footwear at the door. As Lagerfeld once said, “You cannot fake chic, but you can be chic and fake fur.”