Pulling Power

China continues to exert significant influence across Africa, even as the presence of other powers on the continent faces increasing scrutiny. For example, France and the EU are being rejected by military juntas in the Sahel, and Russia’s mercenary-security offerings are met with suspicion by pro-Western African governments. In contrast, China has skillfully maintained a balanced approach.

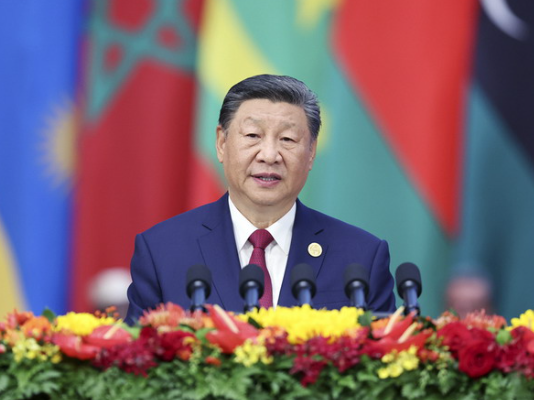

This week, delegations from more than 50 African countries traveled to Beijing for the latest China-Africa summit, known as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac).

The summit attracted numerous leaders, including UN chief António Guterres. Among the attendees were long-time figures like Congo-Brazzaville’s Denis Sassou-Nguesso, as well as newcomers like Senegal’s new head of state, Bassirou Diomaye Faye, who was given a front-row seat next to President Xi Jinping in the leaders’ family photo.

For African governments that resent being pressured to take sides in international conflicts, China has emerged as a dependable partner, willing to collaborate with both Moscow’s allies and civilian-ruled states that lean towards Europe and the US.

While Beijing aggressively pursues its economic interests—demanding access to natural resources in exchange for development support, particularly in infrastructure—it is often criticized for pushing African nations into heavy debt. China has been slow to join global efforts to ease the debt burden on struggling countries and remains unwilling to offer outright debt cancellations.

There are also complaints that China prioritizes its own workers for skilled construction jobs, limiting opportunities for African workers, and that the growing presence of Chinese traders has caused tensions with established commercial communities.

However, for many African governments, these issues are seen as minor. What they value most is Beijing’s willingness to stay engaged across the continent without imposing political conditions, especially in a world that is becoming increasingly polarized.

China’s construction of large-scale transport projects—often avoided by international development institutions and Western investors—continues to draw significant attention. Despite the July 2023 coup in Niger, China remains committed to completing a 2,000-kilometer (1,200-mile) pipeline that will transport the country’s expanding oil production to an export terminal in Benin.

In Guinea, which is also under military rule, the China-based Winning Consortium is making substantial progress on a 600-kilometer railway that will connect one of the world’s largest iron ore deposits at Simandou to the coast. Previous Guinean governments had struggled to secure international support for this project.

At this week’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac) summit, China reinforced this approach, announcing an additional 360 billion yuan ($50.7 billion) in funding over the next three years. However, this time there is a noticeable shift, with a strong focus on the green energy transition, including investments in African manufacturing, particularly in electric vehicles.

This emphasis is both practical and symbolic for a continent that has lagged behind Asia in developing advanced industries. The summit also brought promises of support for other green projects, with President Xi Jinping pledging to launch 30 clean energy initiatives and explore cooperation in the nuclear sector.

The latter commitment touches on a sensitive issue for African observers, who have long resented France’s use of Niger’s uranium to fuel its own nuclear power industry without offering similar opportunities for West Africa. China is also active in Niger’s uranium mining sector, but it remains to be seen whether President Xi’s promise will translate into meaningful projects, given the complex technical and security challenges of the nuclear industry.

The Focac summit also sidestepped some contentious environmental issues, such as frequent accusations that large Chinese fishing vessels engage in overfishing, leaving little for local artisanal fishermen. In a diplomatic move, Sierra Leone’s Fisheries Minister, Princess Dugba, chose to commend the construction of a new fishing port rather than address these concerns.

President Xi Jinping emphasized China’s alignment with the “global south,” highlighting that together, China and Africa represent a third of the world’s population. The summit concluded with the adoption of the Beijing Declaration, aimed at building “a shared future in the new era,” and the Beijing Action Plan for 2025-2027.

Calling for Chinese contractors to return to Africa now that COVID-19 disruptions have ended, Xi announced plans to triple infrastructure projects, create one million jobs, and enhance cooperation across various sectors. However, the specifics of the promised 360 billion yuan in financing—seemingly an effort to boost the Chinese currency’s international standing—remain somewhat unclear.

Of the total, 210 billion yuan ($29.6 billion) will be offered through credit lines, while 70 billion yuan ($9.9 billion) will go towards business investments. Additionally, $280 million in military and food aid was pledged for the entire continent—a relatively small sum compared to the larger economic funding commitments.

The distribution and management of this new financing will be crucial, particularly in ensuring it doesn’t exacerbate debt burdens. Over the past 10 to 15 years, Chinese lending to African countries—eager to advance infrastructure projects—has been widely criticized for contributing to a new debt crisis, just two decades after international debt relief efforts.

In 2016, China announced $30 billion in loans to Africa, often financed through China Eximbank on terms that were typically confidential but likely more expensive than the soft loans from institutions like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, or the African Development Bank, or the grants provided by Western donors.

However, China’s defenders argue that it often financed and built projects in situations where others were unwilling to take the risks or commit the necessary resources. A natural division of labor has emerged, with China focusing on heavy infrastructure, while Western donors and major development institutions support “soft” investments in areas like health, education, skills training, governance, food security, and rural resilience.

As the financial pressures on many countries intensified, especially due to the global economic slowdown caused by the pandemic, the G20 initiated the Common Framework to help indebted nations regain financial sustainability. While China participated in efforts to restructure the repayment burdens of developing countries, critics argued that its contributions were insufficient.

Now, several years later, the recent Focac summit indicates that the situation may be evolving. Just as China stepped in two decades ago to address infrastructure needs that Africa’s traditional donors could no longer meet, Beijing now aims to become a key partner in new high-tech industries and green technology—a scale that many European and North American companies are reluctant or unable to pursue.

While Western investments in Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan regions, remain focused on mining, oil, gas, and agriculture, and Russia continues to provide security services to favored regimes, China is promoting a broader economic vision. However, the question remains whether this vision will lead to real diversification into sectors like green industry, or if the emphasis on large infrastructure projects will continue to dominate.

The future of the China-Africa relationship and whether it will undergo a significant transformation remains uncertain, despite President Xi Jinping’s ambitious rhetoric.