The cost of servicing Kenya’s rising debts has surpassed spending on recurrent expenses for the national government, in part reflecting President William Ruto’s pledge to prioritise obligations to creditors over payments such as salaries.

Treasury spent nearly Sh1.02 trillion on debt repayments in 11 months through May 2023, freshly-gazetted data on expenditure from the government’s main account show, exceeding costs for the day-to-day running of the national government by Sh44.70 billion.

The data indicate payments to creditors grew 11.26 percent year-on-year in the review period to become the single largest expenditure for the government, with recurrent spending falling 4.44 percent to Sh975.12 billion.

This came at a time the Ruto administration has vowed to honour public debt obligations over other recurrent expenses in a bid to instil confidence in international investors of its intent to avoid a sovereign default.

That policy was cited for the delay in payment of salaries for a section of public service employees for March, the first in decades, amid below-target performance in tax collections.

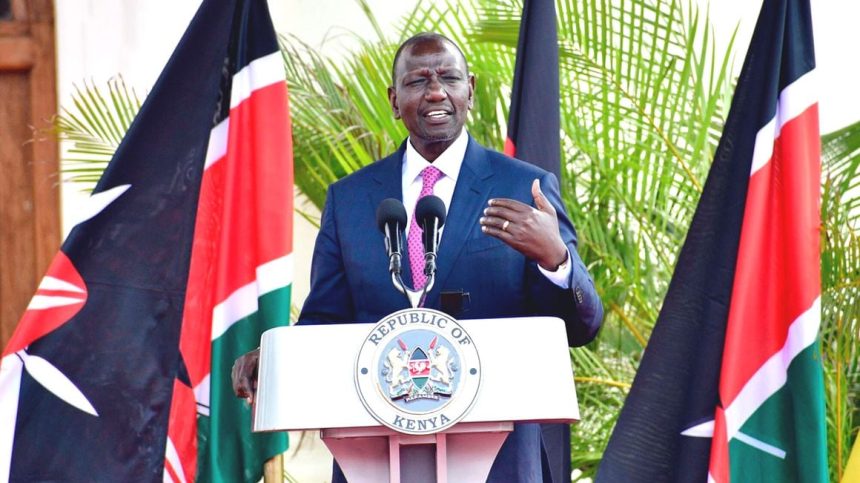

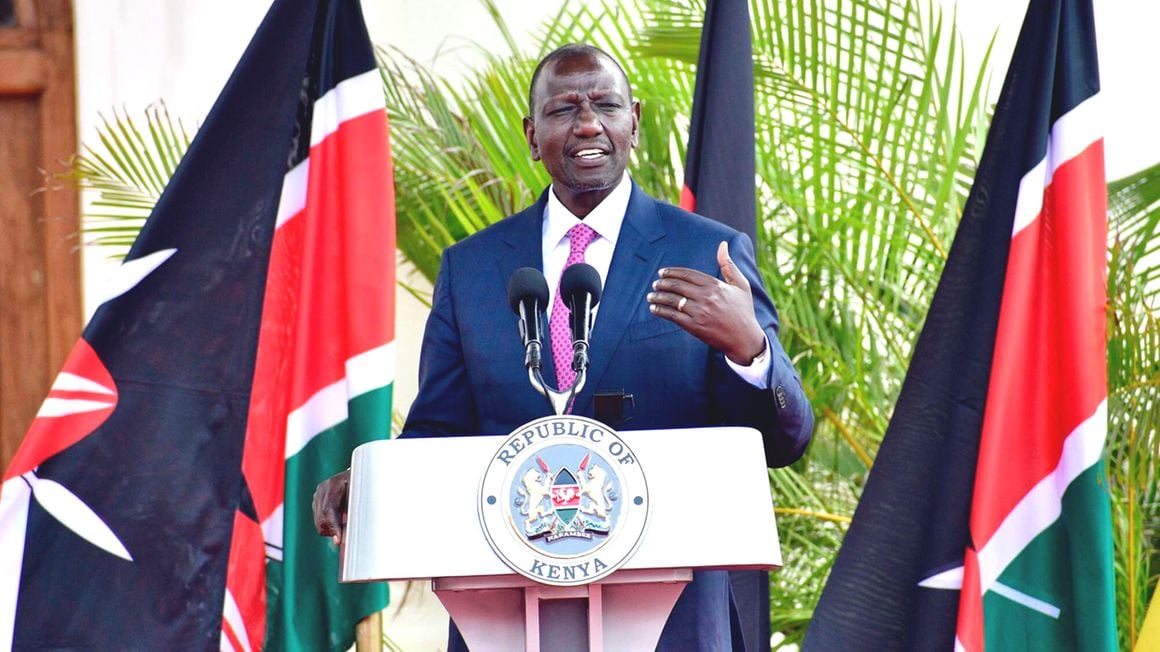

“I am aware of what is happening to other countries. There are countries in our continent that have defaulted in their [re] payments. When I am President, Kenya will not go that route,” Dr Ruto told the last media engagement session on May 14. “You saw there was a slight delay in salaries around April [salaries for March]. Some characters thought I was joking when I told them ‘Listen we are going to live within our means’.”

Servicing costs

The debt servicing costs have been climbing in recent years after the grace period extended by rich countries, particularly China, expired amidst repayments for domestic debt fast falling due.

At Sh1.02 trillion, debt repayments have gobbled an equivalent of 58.60 percent of Sh1.74 trillion tax receipts for the July 2022 to May 2023 period, impeding spending on development projects in a country mired in growing poverty levels and plagued by rising unemployment amongst skilled youth.

This has left little cash for building roads and affordable housing units, revamping the ailing health sector and putting up power plants for cheap electricity — all of which are key for industrial development and the creation of decent job opportunities.

The rising burden of debt servicing costs on taxpayers is a reflection of increased borrowing during the previous administration of Uhuru Kenyatta, in which President Ruto served as his deputy, to build economic growth-enabling infrastructure such as roads, power lines and a modern railway line.

Kenya’s debt binge is underlined by Eurobond offerings, a package of Chinese loans and syndicated commercial loans over the years, which are now squeezing its finances as the loans fall due.

Debt distress

The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have since 2020 classified Kenya at a high risk of debt distress since 2020 as a result of a persistently large deficit in annual budgets in more than a decade, which is bridged through borrowing.

The rising debt obligations have raised jitters amongst international investors over Kenya’s ability to refinance huge external repayments, particularly the $2 billion (about Sh280 billion at the current exchange rate of $1 is equivalent to Sh140) bullet obligations due in June 2024.

“Despite the government’s commitment to fiscal austerity, it may not be able to do enough to avoid a sovereign default over the next 12 months. External borrowing costs are prohibitively high,” analysts at UK-based Capital Economics wrote in a note on Kenya’s economic outlook on June 13. “Political pressures are likely to limit the extent to which the government tightens its belt. The key crunch point comes in June next year when large Eurobond payments are due.”

The Ruto administration is forging ahead with plans to implement Liability Management Operations, largely targeting the 2024 Eurobond in a bid to smoothen the maturity structure of public debt over the medium term.

The Uhuru administration suspended a similar programme aimed at “lengthening the maturity structure and reducing the refinancing risks in the debt portfolio” last year after investors demanded a double interest rate compared to 2021 for a similar issue.

The yield on Kenya’s 10-year Eurobond maturing in June 2024 is still in the double-digit territory and was posted at an average of 13.13 percent for the week ending June 15, a signal of the high-risk profile investors are placing on Kenya’s debt.