The Kenyan government is increasingly borrowing more expensive loans from the domestic market in a trend that has set up households and businesses for a new season of costly loans.

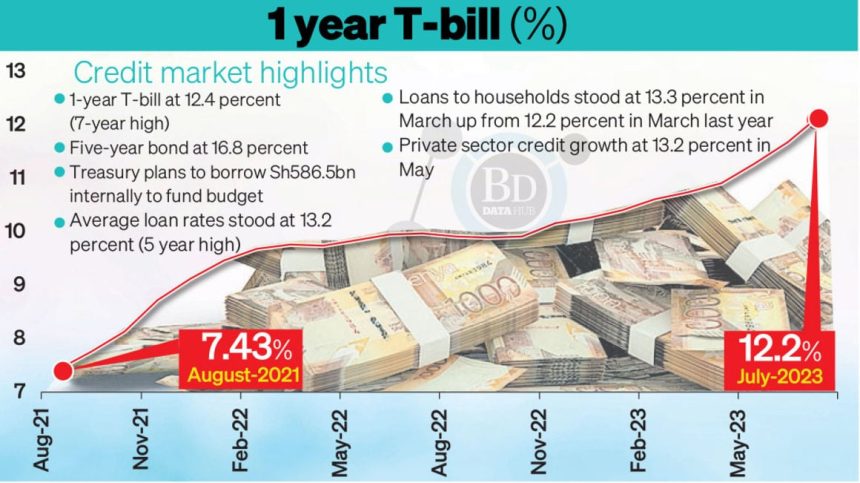

The interest rate on a one-year Treasury bill, which sets the benchmark for determining interest rates charged on other borrowers, peaked at 12.452 percent in this week’s auction whose results were announced on Thursday, representing the highest rate since February 2016.

The borrowing trend points to a government increasingly getting desperate for money to bridge its budget shortfall.

Investors have been demanding higher margins to hold government securities as they factor in the effects of rising inflation on returns at a time when the government is looking to mop up funds from the domestic market after being locked out from external financing by exorbitant interest rates.

Earlier this week, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) had to accept yields of 16.844 percent on a new bond with a tenure of just five years.

With commercial banks basing interest rates charged to customer loans on the government securities return (the reference rate), which is widely regarded as the risk-free rate, borrowers can expect to pay a higher premium to access funds from their respective banks.

The cost of borrowing from commercial banks already set a new high of 60 months in May as borrowers felt the weight of the rising interest rate environment while the average interest rate for a household loan of between one and five years stuck up at 13.37 percent in March.

Nevertheless, the latest interest rates on consumer loans are yet to factor in the effects of recent spikes in the government borrowing rate and the lifting of the Central Bank Rate (CBR) to 10.5 percent from 9.5 percent last month.

Data from the CBK placed the average lending rate at 13.21 percent at the end of May, marking the sharpest rate for commercial bank loans since June of 2018.

While the CBR is on paper the benchmark lending rate, banks prefer to set the cost of loans to customers based on the 364-day paper returns.

A banking insider told the Business Daily that the T-bill rate makes for a ‘good measure of where the cost of money sits’.

With yields on both government securities and commercial bank loans at multi-year highs, analysts are anxious over a potential slump in private sector credit growth as businesses and households are crowded out.

Already the pace of private sector credit growth has become subdued despite sticking to a double-digit rate at 13.2 percent in May, but from a peak of 13.6 percent in July last year.

“We might see banks taking a conservative view which will mean less money to the private sector from banks. The rising yields on lending will only serve to accelerate this eventuality,” Canaan Capital managing director Rufus Mwanyasi said.

“I would expect to see bank lending to the government picking up once more to lift the share of the sector’s holding of domestic debt back to the historical mark of at least 50 percent.”

Banks had trimmed their portfolio allocations towards government securities. The holdings of government domestic debt by banking institutions, for instance, fell to 46.17 percent at the end of June from 48.74 percent at the same stage last year.

The reallocation of assets by banks in the period coincided with the rebound of private sector credit, which had been previously stunted by the interest rate caps.

With the government offering a premium to holders of its securities to keep the money flowing to its coffers, banks are expected to find it easier to pack their funds in the exchequer as opposed to lending to households and businesses.

“It’s about the opportunity cost. Why should I (as a bank) lend to a customer when you can lend to the government at a premium? Lending to the government is cheaper as the alternative has higher costs including the hiring of debt collectors, larger administrator costs and even the opening of branches in some cases,” a banking insider said.

The World Bank has cautioned against persistent crowding out of the private sector due to heavy domestic borrowing by the Treasury.

The multilateral lender noted commercial banks had failed to reach their peak support for investments as the government provided the easy way out by borrowing heavily from the domestic credit market.

“Credit is growing more slowly than GDP, highlighting that the banks’ role in facilitating investments and economic activity remains challenged,” the World Bank stated.

Presently, credit demand in the private sector is holding out against creeping fiscal dominance, with manufacturing, transport and communication, trade and consumer durables sectors registering sustained appetites for credit.

In a mini-survey by the CBK’s Monetary Policy Committee last month, banks noted sustained loan applications and approvals.