With its four-piece bathroom suite, queen-size bed and mini fridge, the untidy prison cell of the notorious leader of the Los Choneros gang, José Adolfo Macías, could have been in a hotel instead of one of Ecuador’s largest prison complexes.

This is “better than at home… [he] lives like a king,” a soldier exclaims in the second of several videos showing Macías’ room and personal grassy courtyard, filled with half a dozen of his pet fighting roosters.

The videos, shared with CNN, were taken in La Regional prison and filmed by members of the military last year.

In another video shot inside Macías’ prison cell, a colorful mural depicting the gang leader better known as “Fito,” warns “silver or lead.”

The phrase, popularized by Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar, offers the grim choice of taking a bribe or being shot – a possible warning to prison staff.

The clips offer more evidence to the stark reality that Ecuador’s prison system has turned into the headquarters for criminal groups that have amassed foot soldiers and influence across the country, experts say.

In less than a decade, organized crime has turned the relatively peaceful country into one of the most dangerous places in Latin America.

Prison massacres have become more frequent in recent years, leading to the deaths of hundreds of people, some of whom were found dismembered.

In the latest riots, more than 130 prison guards and administrative employees were kidnapped across several prisons. They have since been released.

“The criminal groups have all the control [of the prisons] – that’s why Fito had all those benefits in prison: TV, internet, food, alcohol, women – everything he wants,” Jean-Paul Pinto, an Ecuadorian security expert who has previously advised Ecuador’s police and intelligence agency, told CNN.

Experts speculate that those freedoms the drug kingpin enjoyed while incarcerated are also why he was able to escape La Regional prison – a jailbreak that captured the attention of the world and kicked off a storm of violence across the country last month.

Prisons out of control

It was around a decade ago when Ecuador started to lose control of its prisons, experts say. A series of oversights by successive Ecuadorian leaders allowed for criminality to expand throughout the prison system, according to Glaeldys González, an expert on organized crime at the International Crisis Group.

These oversights included mass prison transfers aimed at breaking up criminal groups – a move that backfired and only helped gangs expand their footprint throughout the country, she added.

Mass incarceration policies helped gangs recruit new members behind bars, while the 2017 demobilization of Colombia’s powerful guerrilla force, FARC, allowed Ecuadorian gangs to fill the void when it came to the trafficking of cocaine from Colombia to Ecuador’s ports, analysts say.

With 30,000 gang members estimated across the country, many incarcerated criminals have been able to use influence outside the prison walls to control their jailers.

“Intimidation has been used [by gang members to make prison staff carry out] illicit activity requested by the criminals, who would threaten harm to family and loved ones if they didn’t,” said Julio Cesar Ballesteros, who was formerly the deputy general director of SNAI, and vice-minister of social rehabilitation, under former President Lenín Moreno.

Ballesteros told CNN that corruption was bound to happen because prison guards were underpaid, overworked and dealing with terrible conditions, where overcrowding meant “there weren’t enough guards for the number of prisoners.”

The chronic overcrowding of Ecuador’s prisons has fueled the violence. Inmates have previously told CNN of people having to sleep in corridors without mattresses, and according to data from SNAI, the prisons were between 3,250 and 4,150 people over capacity last year.

Ballesteros added that organized criminal groups “controlled absolutely everything” in the penitentiaries.

“The prisons are no longer administered by the state, from within, the criminals took over…many prison officials, even top officials, were subjected, either by blackmail or threats, so they looked the other way and allowed the illicit activity.”

In one instance, an investigation last year by Ecuador Attorney General Diana Salazar revealed a high-profile incarcerated drug trafficker’s plan to pay off prison staff with up to $3,000 in exchange for bringing in pigs for a “prisoners’ day” party.

Messages shared by Salazar’s office show the trafficker boasting, “It’s like I am the director here,” in messages to acquaintances outside the prison.

It’s part of a pattern across the region, experts say.

“The prison system in Latin America has long been the incubator, and training center, and headquarters for some of the most powerful criminal syndicates in the Americas,” Jeremy McDermott, co-founder of think tank InSight Crime, told CNN.

“And, so, it’s no surprise that this is replicated in Ecuador.”

Drug ballads and cockfighting

Macías is one of Ecuador’s most notorious gangsters and is the only founding member of Los Choneros believed to still be alive.

In 2011 he was sentenced “for a string of crimes, including homicides and narcotics trafficking,” according to think tank Insight Crime, but sprung out of jail in February 2013 before being recaptured months later.

Little is known about his life before crime, but the 44-year-old gained a reputation for being the gang’s money laundering expert while incarcerated for over a decade.

Los Choneros and their main rival, Los Lobos, are believed to be allied with Mexican drug cartels in a war for dominance over Ecuador’s drug trade.

Los Lobos saw an opening amid a violent power struggle in Los Choneros when Macías became its leader in 2020, say experts.

The Los Choneros infighting that year, as well as their turf war with Los Lobos, coincided with an explosion of prison violence and Ecuador’s rising homicide rate – which made Macías a household name in Ecuador.

More than 300 people died in prisons in 2021, some of whom were beheaded in horrific massacres that saw inmates armed with automatic weapons and even grenades. The bloodshed, and rivalries, continue today, González said.

Beyond the prison walls, economic insecurity in the country has either driven many Ecuadorians to crime or forced others to flee the country.

La Regional prison, where Macías was incarcerated before his latest escape, is one of five facilities that make up a large prison complex in Guayaquil – a port city and popular transit route for cocaine leaving the country that has seen some of the bloodiest violence between rival gangs.

In a music video shared online last year, the Los Choneros leader can be seen petting a rooster, apparently inside Guayaquil prison complex.

The drug ballad, sung by Mariachi Bravo, also features Macías’ daughter Michelle. CNN has reached out to SNAI to ask how Mariachi Bravo was able to film the notorious inmate.

Allegations of corruption have swirled around Macías’ luxurious living situation in prison, especially over why he was able to stay in a medium security prison instead of a maximum security penitentiary.

Announcing US sanctions on Los Choneros and Macías this month, the US Treasury Department said the gang leader “enjoyed access to cell phones and internet, which enabled him to continue to direct the activities of Los Choneros and publish external communications.”

A military source told CNN that Macías enjoyed cockfighting while in prison, and that his room was enlarged to be as big as two prison cells.

The drug kingpin was also able to have a string of women visit him while he was incarcerated, the source said.

It was no secret that Macías was living in relative luxury compared to the average inmate.

He celebrated his 42nd birthday with great fanfare, according to CNN affiliate Ecuavisa, which showed footage of a fireworks display at his prison and loud music emanating from the compound.

An image of the event showed the kingpin posing in front of what appears to be a birthday cake.

‘Don’t tell Fito’

In December, the freshly inaugurated Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa joked during an interview with state media that Macías’ cell had more power outlets “than a room at the Marriott.”

Asked what his government’s plan was to tackle the lawless prisons, Noboa replied: “There’s a pretty plan, don’t tell Fito, don’t tell Fito yet.”

The government had planned to transfer Macías to a high security prison. But Macías is believed to have been tipped off in advance, prompting his escape in January.

Around the same time, his wife and children traveled to the Argentine city of Córdoba, where they moved into a recently purchased house, according to officials in Argentina.

“Our theory is that there was previous planning to buy the house, get the family out [of Ecuador], and once the family was out, escape from prison,” Argentina’s Security Minister Patricia Bullrich has said. The family was expelled two weeks after their arrival, according to Argentine officials.

It remains unclear how and when Macías escaped. But the press secretary of Ecuador’s president reckons the Los Choneros leader was told about an impending prison transfer.

“Yes, there was a leak, most likely there was a leak,” Roberto Izurieta told Ecuadorian channel Teleamazonas.

CNN has reached out to the country’s prison agency, SNAI, for comment.

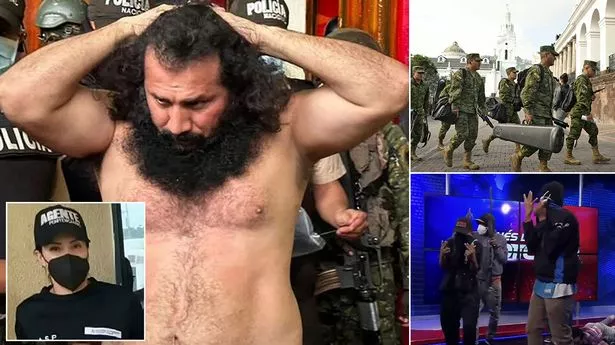

Ecuador exploded in violence following news of Macías’ jailbreak and President Noboa declared a state of emergency on January 8.

Police and prison staff were taken hostage, explosions set off in several cities, a TV studio was raided by gunmen, a prosecutor investigating gangs was murdered, and the alleged leader of the rival Los Lobos gang, Fabricio Colón Pico, escaped prison with dozens of other inmates.

Noboa also declared war on the gangs, which he described as “narco-terrorist groups” who enjoy the support of foreign cartels.

The ongoing crackdown, which has seen the military deployed to help Ecuador’s overwhelmed police force, led to more than 5,000 arrests.

But experts question if such militarization will work as a long-term solution to criminal gangs when the root causes of Ecuador’s violence – including systemic corruption, weak state institutions and being wedged between some of the biggest cocaine producers in the world – have not changed.

Today, soldiers ring the exterior walls of the Guayaquil prison complex where Macías broke out from. As part of the crackdown, Noboa has vowed to build even more prisons.