For a country dangerously addicted to debt as it battles unrelenting inflation, daily weakening of the shilling, tax shortfalls and rising interest rates, the fresh wave of political unrest could push Kenya’s economy to the edge, economists and analysts have warned.

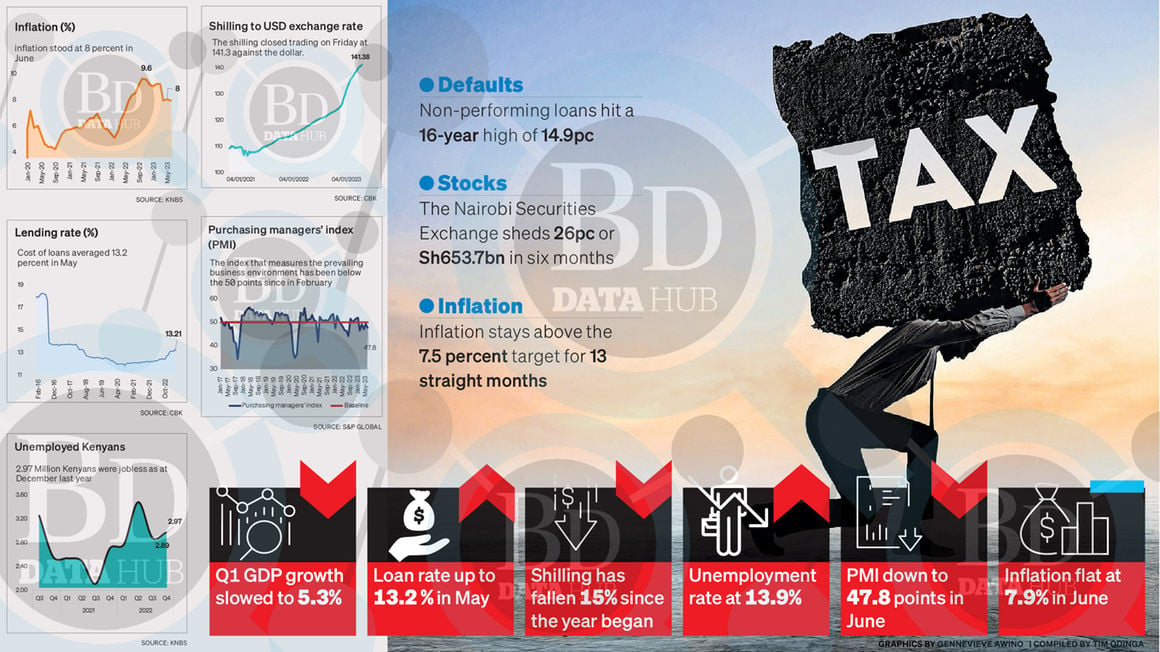

While East Africa’s biggest economy reversed seven straight back-to-back quarterly growth declines to post 5.3 percent growth in the first quarter of the year, economists are cautioning policymakers against being lured into a complacency bubble.

Inflation-adjusted pay cuts are making Kenya’s middle class get poorer while businesses are defaulting on loans after interest rates hit levels last seen seven years ago.

Half a month into the new financial year, the government is still waiting for a court to decide whether it will be allowed to roll out a raft of new taxation measures, including doubling the value-added tax on fuel and deducting 1.5 percent of workers’ gross pay to fund low-cost housing.

The delay in implementing the measures contained in the Finance Act 2023 presents a test for President William Ruto’s government to deliver on the campaign promises he made to Kenyans.

Public policy analyst Robert Shaw says the “crunchy economic times are going to get crunchier,” unless the government maps out and implements a bolder policy to stop the economy from going off course.

“Everything is pointing the wrong way now. We have a government with a huge appetite to collect more but at the same time, with an appetite to spend more. That is almost like a self-inflicted wound,” says Mr Shaw.

“The court case and now the protests are a concern. The protests are affecting economic activities and economic recovery will be jeopardised. Sustained protests will see investors hold back.”

Mr Shaw warns the mass action could “get a life of its own” even in the absence of politicians as the people use this to amplify their frustrations about the high cost of living and rampant unemployment.

The government has tasked Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) to collect Sh2.57 trillion to help in funding a Sh3.58 trillion budget for the financial year that started July 1.

The outlook now looks bleak for the KRA after it missed its revenue collection target by Sh107 billion in the fiscal year ending June 2022, citing a harsh economic environment.

The taxman collected Sh2.166 trillion, a 95.3 percent performance rate. The target was Sh2.273 trillion. Reduced tax collection could see the government, already carrying a Sh9.63 trillion debt as at the end of April, turn to more borrowing or scale down development spending in a move that will hurt growth.

This comes at a time a Sh280 billion bullet payment of Kenya’s debut Eurobond is fast approaching.

The Treasury is forecasting Kenya’s economic growth to expand by 5.5 percent in 2023 up from 4.8 percent last year but is alive to the fact that more citizens are currently confronted with increasingly higher prices of basic commodities, especially food, energy and transport.

Treasury Cabinet Secretary Njuguna Ndung’u said recently the spike in food insecurity and the rise in the cost of living will require “urgent and decisive interventions” especially on the supply side.

However, the return of opposition-led street protests and threats of a prolonged period of civil disobedience will see more dark clouds gather over the economy, according to Ken Gichinga, the Chief Economist at Mentoria Economics.

“The outlook points to a slowdown because we are experiencing many levels of tightening, not only in monetary but also fiscal policy side. When you throw political risk into the equation, it clouds the outlook even further,” said Mr Gichinga.

Political unrest and terrorist attacks linked to Al Shaabab in northern Kenya, have in the past seen foreigners cut or freeze further investing.

The Nairobi Securities Exchange had shed 26 percent or Sh653.7 billion of investors’ fortune in the first half of the year.

The protesters are, among other things, voicing their concerns over the cost of commodities such as sugar and fuel and the planned rollout of new taxes.

Kenya’s cost of living pressure is proving broader and more persistent than anticipated, with the June inflation of 7.9 percent being outside the government’s targeted range of between 2.5 percent and 7.5 percent for 13 straight months.

With Kenya dependent on rain-fed agriculture, scarce rainfall could tear down Dr Ruto’s plan to boost production by subsidising farmers.

Official data show Kenya’s food imports bill in the first quarter of the year hit Sh80.2 billion to nearly match the Sh87.5 billion that was fetched from exporting food, putting at risk the country’s position as a net food exporter.

This means Kenya remains exposed to the movements of food prices such as rice, wheat and maize in the import markets, with potential pressure on the foreign currency and missed taxes in the form of waivers granted to importers.

Banks are also warning of sluggish growth, with the expected weakening of spending power when the Finance Act sets in.

Equity Group chief economist and director of research Yvonne Mhango says the new tax measures speak to tightening fiscal policy, which when added to the ongoing spike in interest rates will soften economic growth.

“A higher tax burden does imply households will have less disposable income. So what we do expect is a slowdown in spending and that has implications on the GDP growth. In terms of businesses, it means a slowdown in retained earnings available for reinvesting and this will ultimately undermine growth prospects,” said Ms Mhango during the recent Equity meeting with investors.

Banks have been increasing their appetite for government papers given the sustained rise in the yields on T-bonds and T-bills.

A new five-year paper, for instance, had a coupon rate of 16.84 percent, a rate that presents a risk for individuals and businesses chasing after bank loans.

Commercial banks have been hiking their loans in line with the central bank rate which is now at 10.5 percent— the highest point in nearly seven years.

Mr Gichinga expects banks to give more attention to the government at the expense of the private sector where the non-performing loans ratio hit a 16-year high of 14.9 percent in May.

He says with rates on government paper getting higher, investors will at some point start asking whether it is going to be possible for the Treasury to raise money to pay them on time.

“In the fullness of time, the investors, using risk models, will start questioning how the government will be able to raise revenue to service debt redemptions when businesses that are supposed to raise that revenue are struggling,” says Mr Gichinga.

The government has struggled with paying civil servants on time and releasing money for other key activities such as running counties, paying pensions to retirees and footing hospital bills for people insured by the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF).