A snap election was called following a fatal helicopter crash, injecting an element of suspense and unpredictability into Iran as voters head to the polls to select a new president. Elections in the Islamic Republic are tightly controlled, with candidates vetted by a powerful clerical committee before being allowed to run.

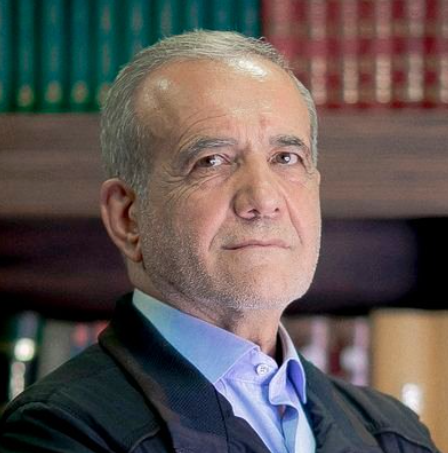

Voter apathy has been widespread recently, but this time, there is a wildcard: Massoud Pezeshkian, a reformist former heart surgeon and health minister. Pezeshkian has criticized Iran’s morality police for enforcing strict dress codes on women, calling their actions “immoral.”

He has pledged to improve relations with the West and revive nuclear talks to end sanctions crippling Iran’s economy. Pezeshkian has garnered public support from former reformist presidents Hassan Rouhani and Mohammad Khatami, as well as former foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif.

His campaign rallies have drawn increasing crowds leading up to election day. Recently, two candidates withdrew from the contest, seemingly to prevent splitting the conservative vote. Latest polls showed Pezeshkian leading over Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, a former Revolutionary Guards commander and current parliament speaker, and Saeed Jalili, a hardline former nuclear negotiator.

Conservatives, who oppose Western engagement, argue Iran can thrive despite sanctions. Another candidate remains in the race to succeed Ebrahim Raisi, who died in a helicopter crash last month along with seven others. Turnout figures are considered crucial for assessing the Islamic Republic’s legitimacy, having hit record lows in recent parliamentary and presidential elections.

Supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei – who is the ultimate authority in Iran – has called for “maximum” turnout. And a solid core of regime supporters are sure to vote.

But many young and middle-class Iranians are deeply disillusioned and distrustful of any political process organised by the Islamic Republic, and now want an end to 45 years of clerical rule.

“There are lots of billboards in the streets asking people to ‘vote for a better tomorrow’, but we just don’t buy it any more,” a 20-year-old student in Tehran told me via text message. “Nobody wants to vote any more.”

Since the tragic death of Mahsa Amini, a young woman in custody of Iran’s morality police in 2022, and the subsequent nationwide protests it ignited, the divide between Iran’s leadership and its people has widened significantly.

The harsh crackdown on protesters has intensified animosity toward the regime, especially among Generation Z. Previous hopes placed on reformist movements have repeatedly been disappointed, with advocates for systemic change finding themselves increasingly marginalized in recent years.

Even former president Hassan Rouhani was barred from running in recent elections for the Assembly of Experts, a key body responsible for appointing the Supreme Leader. This has led many Iranians to lose faith in the prospect of achieving meaningful change through electoral means.

“I won’t vote this year,” a 70-year old woman in Tehran, who has previously voted for reformist candidates, told the BBC. “I know nothing will change. The economy is in such a dire state and a generation of young people now just want to leave Iran.”

Azad (not her real name), a women’s rights activist jailed during the protests, described it as an “electoral circus”.

“When the puppeteer is a single person named Khamenei, it makes no difference what name comes out of the ballot box,” she told me over a social media app. “At the peak of the unrest, people repeatedly chanted this slogan in the streets: ‘Reformist, conservative, the game is over’.”

Some believe that the clerical establishment only allowed Mr Pezeshkian to stand as part of an effort to boost turnout.

Azad described it as a “game” being played by the regime. “We don’t trust them and we don’t want to be manipulated again.”

Several people in Tehran I have spoken to over the past few days have echoed that view.

“It’s a duty to vote but I won’t,” a law student told the BBC. “Because all previous elections showed none of the elected presidents made anything better for people.”

But others may be enticed to the polling station by the small glimmer of hope for change that Mr Pezeshkian represents for liberal-minded Iranians.

“I’ll be voting for Pezeshkian,” Maryam, 54, from Tehran says. “I believe that change can only come from inside Iran – through reform.”

She likes the fact that his background is not in the security forces and that he’s “clean”, with no allegations of corruption against him.

She also hopes he can improve Iran’s relations with the outside world, and believes he will win.

If he does, there is a huge question mark over what room for manoeuvre he will have.

“Pezeshkian is a reformist in name only,” says Sanam Vakil of think-tank Chatham House.

“He supports the Islamic Republic and is deeply loyal to the supreme leader. His participation could potentially boost public turnout and increase enthusiasm, but one should not expect much more than a difference in tone should he be elected.”